BRIDGING THE LANGUAGE HERITAGE OF

THE OLD WORLD WITH THE NEW WORLD

As the theme of this discussion was mostly historical & decidedly Shakespearian later on, our gentlemen were elevated to the NOBLE LORDS team and the Ladies (surely already “fair” in every way) became the FAIR LADIES team! At stake was the prestigious ‘PORTLAND CUP’ which Sheila awarded to one team at the end of our session!

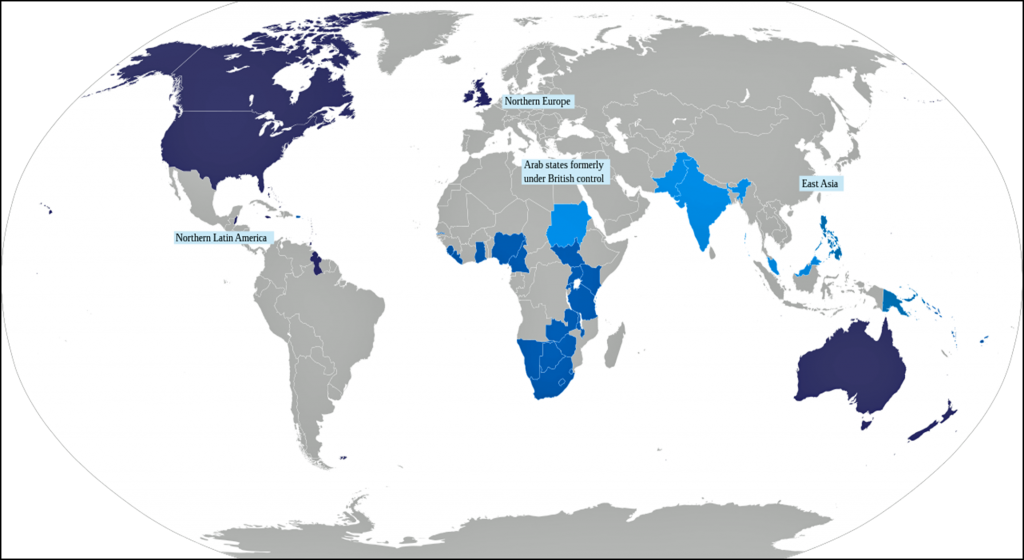

To start, we reflected on our SHARED LINGUISTIC HERITAGE, as an international group of speakers, readers, and writers, who live not just in the USA & Great Britain but in:

THE ANGLOSPHERE

This is a region on our planet which gives us a shared LINGUISTIC IDENTITY as ANGLOPHONES. We inhabitsomewhere in the world where English is the dominant language and therefore we belong to the WORLD-WIDE FAMILY of ENGLISH-SPEAKING PEOPLES.

This means that we ANGLOPHONES can lay claim to a WORLD LANGUAGE as our own. For English is the OFFICIAL LANGUAGE of more than 75 countries, the major foreign language taught in most schools, the language of political negotiations and international business and the International Language of Science and Medicine. International Treaties even require that all passenger airplane pilots must speak English!

From the Anglosphere’s lowly beginnings in England and the Scottish Lowlands, English in its modern form spread around the world from the 17th century onwards

Through all types of printed and electronic media, it has become the GLOBAL BRIDGE LANGUAGE for international discourse, greatly assisting communication as their official “Lingua Franca” in countries such as INDIA, where an estimated 454 native languages are spoken by 1.38 BILLION people who would otherwise be incomprehensible to one another.

Since Sheila requested us, in our February meeting, to declare ourselves officially as ‘writers,’ it seems we are honoured to be servants of this mighty linguistic force in our world, so it’s good to understand as much as we can about this great ‘mistress’ we all serve.

ORIGINS

NOW FOR SOME DEEPER SOURCES

To find out how English became so popular, we must travel back in time about 5,000 years to the Black Sea in Southeastern Europe, where people spoke a mysterious language called PROTO-INDO-EUROPEAN which is no longer spoken and researchers do not really know what it sounded like.

Yet, Proto-Indo-European is believed to be the ANCESTOR of most European languages. These include the languages that became: a) Ancient Latin, b) Ancient German and c)Ancient Greek.

- Ancient

Latin disappeared as

a spoken language. Yet it left behind three spoken languages that became

Modern Spanish, Modern French and Modern Italian. - Ancient

German became Dutch,

Danish, German, Norwegian and Swedish, making many of the

ingredients for ENGLISH in the British Isles, as a result of multiple

invasions over many hundreds of years. - Ancient

Greek, however,became

a civilised source of scholarly borrowing for our Renaissance

‘intelligentia,’ as most courteously on their part, the Ancient Greeks

refrained from joining the hordes of invaders who linguistically clobbered us

into submission!Instead, our scientific and cultural communities have

borrowed liberally from the Ancient Greeks to create ‘NEOLOGISMS’, i.e.

newly invented words, that never existed in Ancient Greek, such as

‘telephone’ ‘psychology’ ‘photography’ ‘philharmonic’ etc and most recently

the ‘metaverse.’

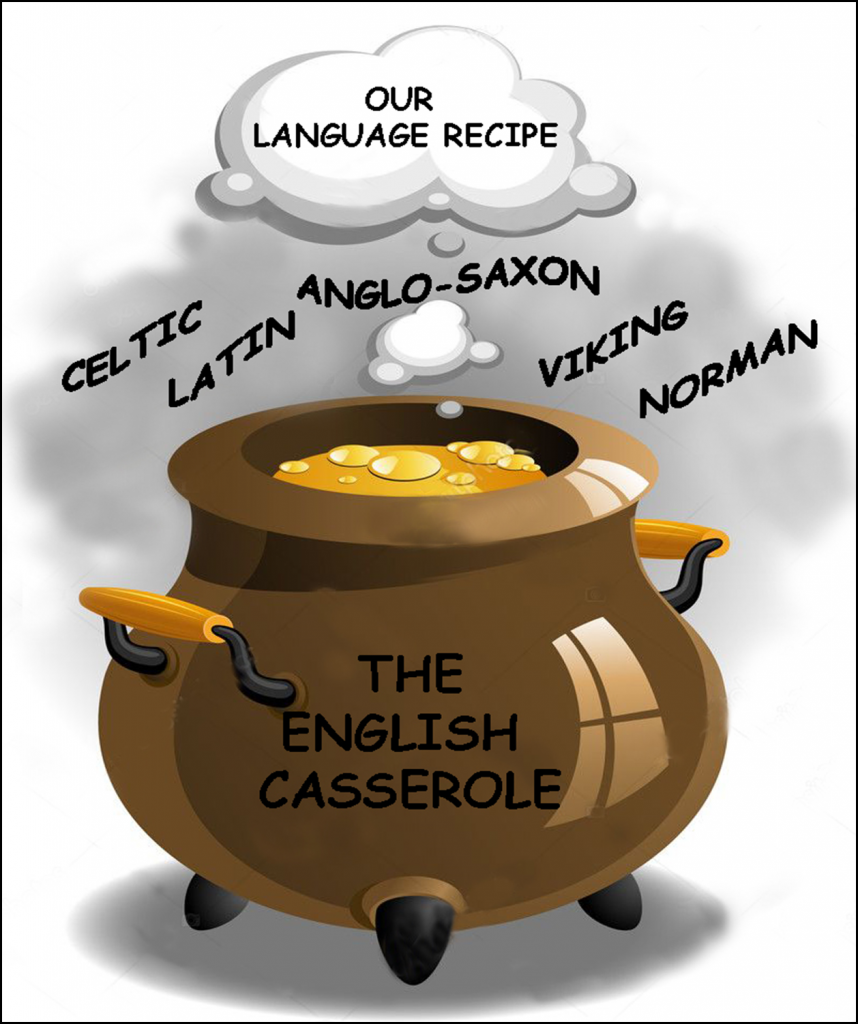

THE INVASION CASSEROLE

Now we examined the RECIPE of ‘ Invasion Ingredients’ that make up our English ‘casserole’, because it explains so many baffling anomalies about how we speak, write and most particularly how we SPELL, which led us to some fun and games later, when the Lords and Ladies were each challenged to give it a bit of ‘stir’!

1) THE CELTIC INVASION

The unsuspecting Ancient Britons first had to contend with the CELTS from Europe in 400 BC

The Celts contributed 3 MAJOR CELTIC LANGUAGES which still survive intact today on our island: a) Irish Gaelic, b) Scots Gaelic (pronounced Gallic), and c) Welsh, none of which have any discernible resemblance to English! For example “Thank you friend,” in Scottish Gaelic is “Tapadh leat a charaid”( pronounced ‘tah-per late a carriage’) Sound familiar? I doubt it! How about this famous phrase in Welsh: “Ein Tad, yr hwn wyt yn y nefoedd” -The beginning of the Lord’s Prayer.

The Celtic tribes lived very close to Nature and so their languages were natural and idiomatic rather than formulaic and systematised. Their speech patterns meandered with the fluidity of rivers being constantly deflected by random stones. So when the Romans invaded, speaking their super-logical Latin, there was very little linguistic compatibility, which is one reason why only tiny sprinklings from Celtic languages can be traced in our English casserole.

2) THE ROMAN INVASION

The second invasion of Britain was by the ROMANSled by Julius Caesar in 55 BC. He only stood our terrible weather for a year then scurried back to sunny Gaul in 54 BC, so there was not much time for Latinising the speech, until 43 AD when the Emperor Claudius began his three and a half century (367 year) occupation of Britain, driving most Celts to WALES, SCOTLAND and IRELAND. Meanwhile in ENGLAND the Latin flavouring was thoroughly stirred through our whole language like strengthening stock.

But suddenly, the Romans were ordered to hurry home to defend Rome in 410 AD, scattering their prefixes and suffixes behind them like tasty Latin crumbs over our conquered regions.

The word got round that Britain was now a vacant piece of real estate up for grabs so:

3) THE INVASION OF THE ANGLES

About 1,500 years ago, our third invaders, who contributed a great dollop to the language ‘RECIPE’ were the ANGLES, a Germanic tribe.

4) THE INVASION OF THE SAXONS & JUTES

Shortly after, two more groups crossed to Britain. They were the SAXONS and the JUTES whose languages stirred in well and dissolved very effectively.

(Incidentally, the CELTS really had fought valiantly against all these new invaders but once settled in Scotland, Wales and Ireland, their languages separated into distinct Celtic variants, until the VIKINGS struck the Celts from the North. In WALES and IRELAND, CELTIC WELSH and IRISH GAELIC are taught with pride in schools today and widely spoken. But SCOTS GAELIC (GALLIC) is generally taught and spoken only in the HIGHLANDS and ISLANDS of SCOTLAND, where it is a treasured heritage.)

Meanwhile, back down in England, the SAXONS, ANGLES & JUTES mixed their different languages. The resulting ANCIENT CASSEROLE became what we call:

ANGLO-SAXON or OLD ENGLISH.

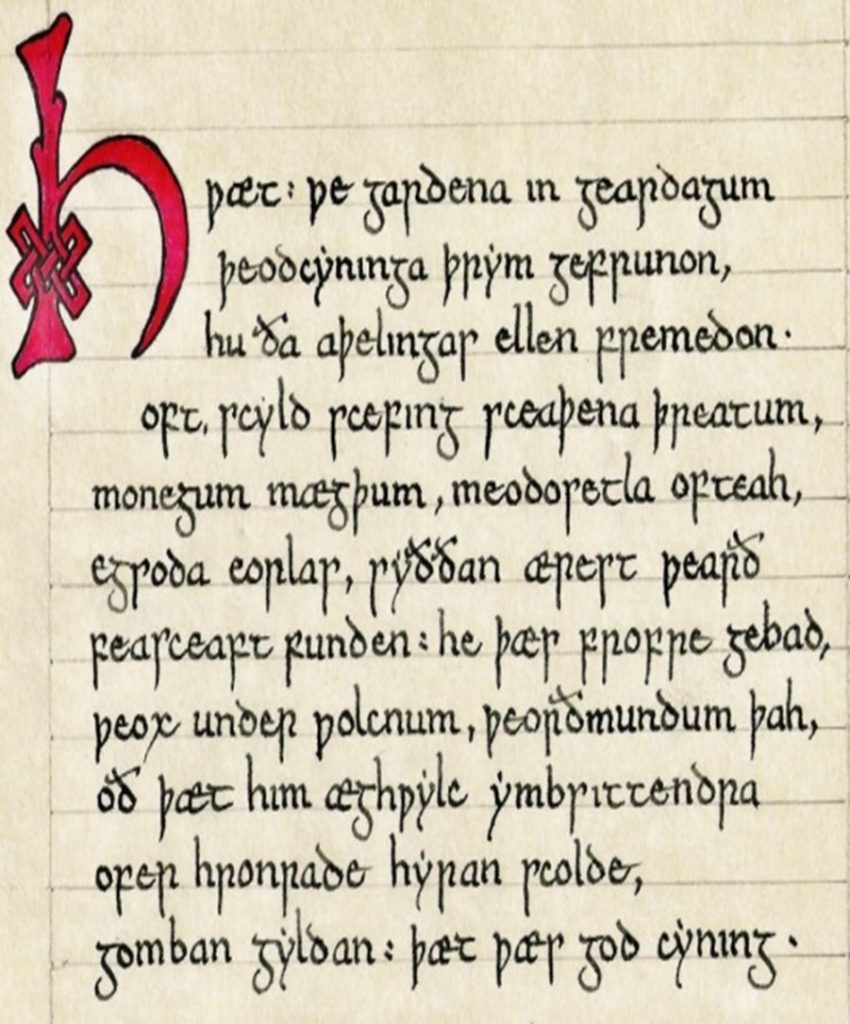

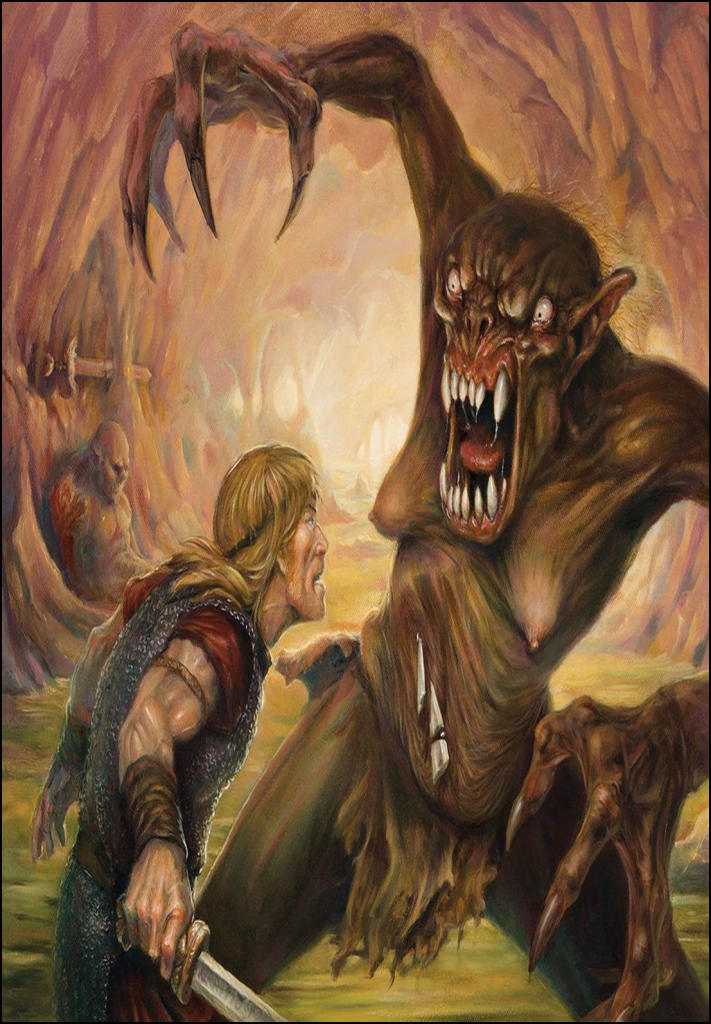

Old English is extremely difficult to understand. The most famous written work which has survived from that Old English period was the first known English poem, written more than 1,000 years ago, author unknown. It narrates the story of a great king, Beowulf, who fought against monsters, and a page from it is reproduced below.

Lyndsay challenged us to find the four words which mean

“That was a good king”

(CLUE: there were no articles yet (a, an, & the) and the first letter of the phrase, which looks like a “P” is in fact a “THORN,” the Anglo-Saxon letter for “TH.” Their “W,” which begins the next word, looks similar to the ‘thorn’ but not so tall.

They are the last 4 words on the page: “paet waes god cyning”

5) THE VIKING INVASION

The next great invasion of Britain which added very significantly to the ‘RECIPE’ was the arrival of the fearsome VIKINGS who came about 1,100 years ago from the far north, mainly Norway and Denmark.

Silent G or K at the beginnings of words are also of VIKING origin: ‘gnash’ ‘gnome’ ‘gnat’ ‘gnu’ and ‘knee’ ‘know’ ‘knife’ ‘knit’ ‘knuckle’ etc.

So, What is the missing “Viking” silent letter in this phrase: ‘A tree _ nawed by rabbits.’

And which missing “Viking” silent letter completes this notorious Nursery Rhyme thief: ‘The _nave of Hearts.’

Vikings SOUNDED those letters, but only the English speakers were literate enough to WRITE them, ceasing to pronounce over time what did not fit in with the evolving ‘soundscape.’

This has left us as ‘writers’ with the spelling headache created by our “GHOST” letters. For it is an established principle that SPELLING tends to OUTLIVE PRONUNCATION, the latter leaving its SILENT GHOSTS behind, whose awkward SOUNDS were droppedfor convenience of usage.

6) THE NORMAN CONQUEST

The 6th occupation of Britain was by the NORMANS, more than 900 years ago.

It was led by which William the Conqueror, in 1066.

This was a real game changer for our language and particularly for some of the spelling differences between Britain and America, which we’ll see later.

The NORMANS, a French-speaking people from the north of France, became the new rulers of Britain. These new rulers spoke only French for several hundred years. So FRENCH was now the most important language in the world! It was the language of EDUCATED people whilst the common people of Britain still spoke Old English.

The invisible hand was now stirring up a huge number of Norman-French ingredients into our recipe.

Some of these include “damage,” “prison,” and “marriage.”

Most English words that describe Law and Government come from Norman French: words such as “jury,” “parliament,” and “justice.”

One theory says that, since the rich ate meat, our meat words come from French. Meanwhile the poor cared for animals and used Germanic words. Hence, Cow (kuh) vs beef (boeuf), swine (schwein) vs pork (porc), sheep (schaf) vs mutton (mouton).

But by 800 years ago, the ruling Normans no longer spoke pure French. Their language had become diluted into a MIXTURE of French and Old English, which blended and marinated into what we call MIDDLE ENGLISH.

Middle English sounds slightly like Modern English, but it is very difficult to understand. But at this time the FIRST REALLY IMPORTANT WRITER to use the English language emerged, a poet who lived in London and died there in 1400 – Geoffrey Chaucer, who wrote “The Canterbury Tales.”

Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales were written more than 600 years ago and give a clear picture of the people of his time. His characters all seem very real; some wise and brave, some stupid and foolish, some mean and proud, all travelling to the town of Canterbury on pilgrimage. He certainly teaches us a great deal about characterisation in our writing.

Moving on another 100 years to around the year 1500, thanks to RENAISSANCE-era ‘loans’ from Latin and Greek and also a phenomenon called the Great Vowel Shift, which affected the qualities of most long vowels, Middle English finally evolved into EARLY MODERN ENGLISH.

THE WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE FACTOR

Now our Anglophone tongue is about to be so transformed that centuries later, George Bernard Shaw would be able to define its “majesty and grandeur” as:

“the greatest possession we have.”

For at last, we have reached the LANGUAGE RECIPE consumed and cooked up for us by WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, to whom we ANGLOPHONES owe the most enormous debt of all!

He invented 1,705 new words

Astonishingly, they are still in use today in our daily speech.

Shakespeare created either by changing nouns into verbs, or changing verbs into adjectives, connecting or blending words never before used together, or by adding prefixes and suffixes, and also by devising words wholly original.

Here are just 7 examples with their sources:

- Bandit. Henry VI, Part 2. 1594.

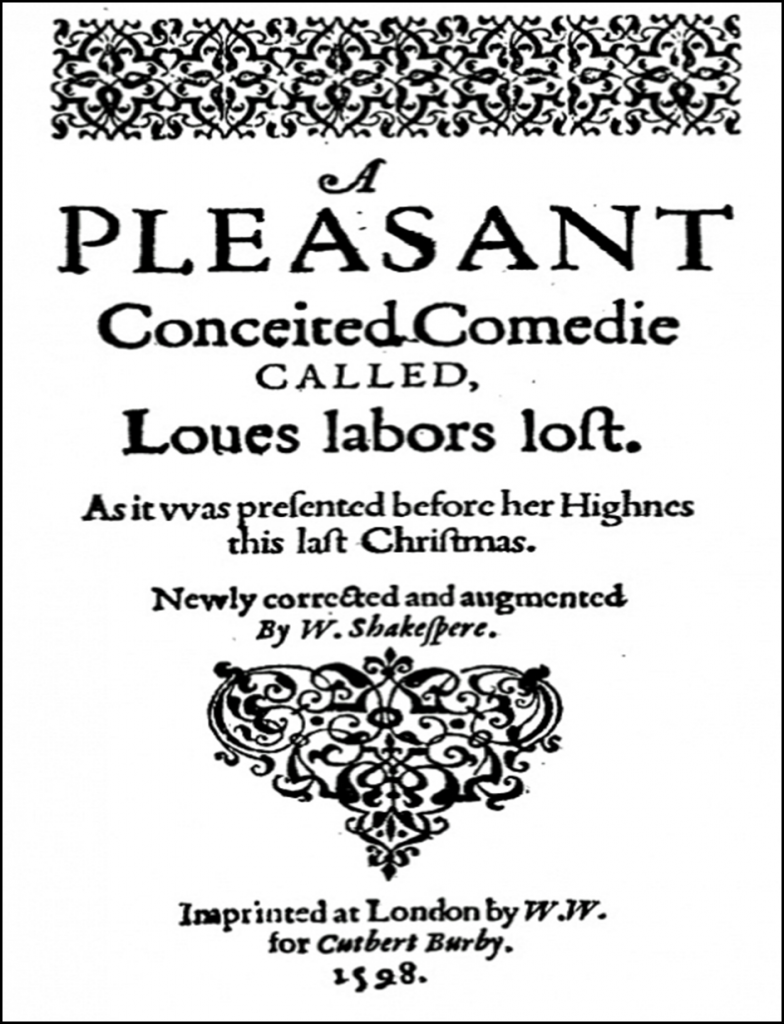

- Critic. Love’s Labour Lost. 1598.

- Dauntless. Henry VI, Part 3. 1616.

- Dwindle. Henry IV, Part 1. 1598.

- Elbow (as a verb) King Lear. 1608.

- Lacklustre. As You Like It. 1616.

- Lonely. Coriolanus. 1616 (a new ADJ invented from the ADV or ADJ “alone.”)

So many everyday words are owed to him, such as accommodation, amazement, bump, control, countless, courtship and that’s just some of his ABCs on his list.

Interestingly he also conjured up a few odd rejects that never caught on and we can only guess what they mean: ‘armgaunt’, ‘pajock’, ‘wappened’, to name but 3 words we never say!

- ‘armgaunt’= having skinny arms ( Ant & Cleo)

- ‘pajock’=peacock ( Hamlet)

- ‘wappened’ = violated or deflowered ( Timon of Athens) “What makes the

wappened widow wed again?” - So Shakespeare invented his own Elizabethan “F” word!

We all do this anyway to make new words. There is now the established word ‘BREXIT’ created from ‘Britain+Exit’ (from the European Union) added to the Oxford English Dictionary in 2016. Less famously, Lyndsay teaches choir for Sheila’s brother Martin and sometimes the song-lyrics require a bit of re-working to give the high notes more open vowels. Martin once quipped amusingly: “I think this piece needs “Lyndsayfying” ie: re-jigged by Lyndsay! You won’t find that word in any Dictionary!

SHAKESPEARE’S IMPACT

So just how influential was this one individual, the person we Anglophones deem the greatest writer who ever lived?

Was he simply a born prodigy, a naturally brilliant writer at school from the “get-go?”

Ben Johnson, one of his contemporaries certainly didn’t think so, commenting that despite enduring a 12 hour school day, 6 days a week at Stratford Grammar School, Shakespeare had “small Latin & less Greek” two of the principal subjects in the Elizabethan Liberal Arts Education.

Shakespeare’s classroom in Stratford-On-Avon

But the fact that it is English, rather than Latin and Greek, which now steers all the learners in the ANGLOSPHERE through the educational process is due in no small part to Shakespeare personally seizing our language at the helm.

THE RENAISSANCE EFFECT

But something else rather special was in the air when Shakespeare was growing up. The RENAISSANCE was just catching on in England (everybody else had it a century before,) so Shakespeare’s education also benefited from a classically-inspired RENAISSANCE subject known as the “FIGURES OF RHETORIC.”

‘The School of Athens’ by Raphael

These are a set of formulas from Ancient Greek culture for producing great lines, not by saying something different, but by saying something in a different way. (Lyndsay said she owes a great deal here to the book Sheila recommended at our February meeting: “The Elements of Eloquence” by Mark Forsyth, which we heartily endorse.)

After all, the business of producing ‘great lines’ is something we’re interested in. But we writers of humbler provenance expect to start badly at them, then gradually improve. We don’t expect this of Shakespeare, do we?

Nevertheless, he started rather shakily, like most people starting a new job. I won’t ask you to come up with a memorable line from Henry VI Part 1, one of his very first plays, because there weren’t any. But each successive play has more and more great lines in it.

So never listen to people who tell you that great writing cannot be learned because Shakespeare himself got better and better, by practising and reworking learned techniques for making single phrases striking and memorable.

So let’s zoom in on his mature application of Rhetorical Technique in an extract from his 32nd play out of his total of 37: “Anthony and Cleopatra”

The Meeting of Antony & Cleopatra by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema

Shakespeare owned a precious translation of Plutarch which he used for his historical research for this play. This is exactly what he read in his Plutarch book about Cleopatra

“She disdained to set forward otherwise but to take her barge on the river Cydnus, the poop (the nautical term for the rear of a ship!) whereof was of gold, the sails of purple, and the oars of silver, which kept stroke in rowing after the sound of the music of flutes, howboys, citherernes, viols and such other instruments as they played up in the barge.”

“Great data!” thought Shakespeare, “I’ll steal that for my play!” But of course he had to ‘Shakespearify’ it first! (there’s a nice invented word!) Let’s see what he did:

“The

barge she sat in like a burnished throne,

Burned on the water: the poop was beaten gold:

Purple the sails and so perfumed that

The winds were lovesick with them; the oars were silver,

Which to the tune of flutes kept stroke, and made

The water which they beat to follow faster,

As amorous of their strokes.”

Wow! How did he transform Plutarch’s basic factual description so magically and make it dazzle us? Apart from the poetic metre, he did it mainly by the application of one single ‘Figure of Rhetoric’ which we have all unconsciously used ourselves, because people naturally love to hear words that begin with the same letter. ALLITERATION.

So he made her ‘barge’ ‘burnished’ and let it ‘burn’ upon the water, adding ‘beaten’ to her golden poop. And of course he was careful not to overdo the effect as that ends up rather silly. So he finished with the ‘Bs’ and turned to the ‘Ps’, picking up the ‘poop’ and ‘purple’ sails from his Plutarch book and making them ‘perfumed’– masterly! Plutarch just listed all the instruments and wrote ‘after the sound’ which Shakespeare alliterated musically into ‘to the tune.’ He cut down Plutarch’s raucous orchestra to just the ‘flutes’ because he liked the airy sound of the word ‘flutes’ making the “water which they beat to follow faster, As amorous of their strokes.” He bathed our senses in ALLITERATION like the water of the Nile.

As if all of the words Shakespeare invented were not enough, he also constructed many pithy sayings and idioms using everyday common words. They have survived the centuries and are in such general use today that we are unaware that we are speaking Shakespearian all the time without realising it.

So let’s get talking some Shakespeare together while still remaining modern people in 2022!

“Knock! Knock! Who’s there?”

(Macbeth)

An Everyday Shakespearian Conversation

Kate (named after Katherina in “The Taming of the Shrew”) has just been jilted. Her friend Ben (named after Benedick in “Much Ado about Nothing”) has just knocked on her door to “lend an ear.” (Julius Caesar) Incredibly, all the colloquial phrases spoken between them(highlighted) are directly lifted from Shakespearian plays, written by the Bard over 400 years ago!

KATE: I’m “in a pickle” Ben!(The Tempest) He’s just made “short shrift”(Richard III) of me!

BEN: Well Kate, “The course of true love never did run smooth.” (A Midsummer Night’s Dream)

KATE: But I was a “Ministering Angel” (Hamlet) to him. Every night, I cooked him “a dish fit for the gods,”(Julius Caesar)yet he’s moved out, “bag and baggage,”(As You Like It) “without rhyme or reason!” (As You Like It)

BEN: Still, it was “a foregone conclusion”(Othello) that he was leading you up “the primrose path!” (Hamlet)

KATE: I must have been “living in a fool’s paradise.” (Romeo& Juliet) He’s “played fast and loose”(Love’s Labour’s Lost) with me.

BEN: “The world’s your oyster” (The Merry Wives of Windsor) now, Kate!

KATE: But he “made a laughing stock”(The Merry Wives of Windsor) of me.

BEN: “For goodness sake!”(Henry VIII) He was “eating you out of house and home!”(Henry IV Part 2) It was “high time”(A Comedy of Errors) to “send him packing.”(Henry IV Part 1)

KATE: He’s already left town. It all happened “in the twinkling of an eye.”(The Merchant of Venice)

BEN: “Good riddance!”(Troilus & Cressida)I always thought he was a “blinking idiot,”(The Merchant of Venice) His voice was enough to “set your teeth on edge!”(Henry IV Part 1)

KATE: Well, he’s “had his day.” (Hamlet) After all, “the truth will out!”(Merchant of Venice)

BEN: But in future, don’t “wear your heart on your sleeve.”(Othello)

KATE: Thanks Ben. You’re “a tower of strength,” (Richard III) a real “heart of gold.”(Henry V) But all that’s left for me now is to “lie low.”(Much Ado About Nothing)

BEN: Poor Kate! His “barefaced”(Macbeth) cheating has made you such “a sorry sight.” (Macbeth)

KATE: No wonder! The “sanctimonious” (Hamlet) way he “hoodwinked”(Romeo & Juliet) me has “made my hair stand on end” (Hamlet) andI haven’t “slept one wink.” (Cymbeline)

BEN: But you two were always such “strange bedfellows.”(The Tempest)Whatever did you see in him? “It’s Greek to me!” (Julius Caesar)

KATE: Well they do say “love is blind.” (Two Gentlemen of Verona)

BEN: True, but that’s rather a “cold comfort.”(The Taming of the Shrew) Where is he now?

KATE: I’ve no idea. Since he “vanished into thin air,”(Othello) I can’t stop thinking of him, though “more in sorrow than in anger.” (Hamlet) I’m just so “lonely.” (invented in Coriolanus)

BEN: “What’s done is done,”(Macbeth) so try to “make a virtue of necessity.” (Two Gentlemen of Verona)

KATE: I’ll try, but I’m just too “fainthearted.”(Henry VI Part 1) I should be “made of sterner stuff.”(Julius Caesar) But what if he wants me back?

BEN: Don’t “budge an inch!” (The Taming of The Shrew) It’s “high time”(Comedy of Errors) you were “fancy free!”(A Midsummer Night’s Dream)

KATE: You’re right! Anyway, “What the Dickens!”(The Merry Wives of Windsor) “I’ve “danced attendance” (Henry VIII) on him long enough! I’ll put him behind me “come what may!” (Macbeth) By the way Ben, please keep all this to yourself.

BEN: “Mum’s the word!”(Henry VI Part 2)

As you see, our OLD WORLD ETYMOLOGICAL CASSEROLE which we’ve stirred up for you over here is now positively simmering!

Unsurprisingly, after all that churning change in our linguistic mixture there was some letter-spillage. In this section we are going to look at some odd little splashes left behind, which we call:

GHOST-BUSTING!

exorcising the “GHOSTS OF ‘PRONUNCIATION PAST”)

- Why did we RETAIN the spellings of

SILENT LETTERS long since after ceasing to sound them? - It was for the purpose of

TRANSLITERATION in an increasingly literate world.

For there is something about SPELLINGS that makes us want to preserve them in order to feel connected to our language’s originators from Scandinavia and the heartlands of Europe, who have not only contributed their ingredients into our precious language, but have also donated to our gene-pool.

Their original texts had now become OUR HERITAGE and every word written there was a kind of ‘SOUNDSCAPE PHOTOGRAPH’ bequeathed to us from our ANCIENT PAST. Imagine how excited you would be to come across an old photo with a GHOST clearly visible on it? You’d never erase it.

So we can say that SPEECH constantlyEVOLVES and settles into LOCAL variants, whereas SPELLING & WRITING SYSTEMS eventually become FIXED and settle into NATIONAL NORMS.

Now you’re in for a CHALLENGE as READERS in our OLD WORLD where so many of those left-behind letters really do ‘HAUNT’ our words, as we see in this challenge:

What are the three hardest things to say?

- I was wrong.

- I am sorry.

- Worcestershire sauce (Wuster sauce)

That’s just our sauce! Now each team was challenged to read 6 of our OLD WORLD LOCATIONS with a possible 6 points to win for the team! They’re rather whacky, so just throw all phonetic logic out of the window, as you can see! (For linguistic revenge, the NEW WORLD hits back hard with ARKANSAS, TUCSON and CONNECTICUT, to name but three which certainly trip us up!)

| LOCATIONS IN ENGLAND | |

| NOBLE LORDS | FAIR LADIES |

| BICESTER (in Oxfordshire) (Bis-ter) | HAPPISBRUGH(in Norfolk)(Hays-bruh) |

| CHOLMONDELEY (in Cheshire) (Chum-lee) | MAGDALEN ( University College) (Maud-lin) |

| LEOMINSTER ( in Herefordshire) (Lem-ster) | BELVOIR ( a castle in Grantham) (Beaver) |

| Now let’s raise the bar to an even greater challenge which awaits you from the Gaelic Ghost-letters of SCOTLAND! | |

| LOCATIONS IN SCOTLAND | |

| CULZEAN ( a castle in Ayrshire) (Kull-ane) | WEMYSS (a coastal village) (Weems) |

| HAWICK ( a Borders town) (Hoyk) | ISLAY( a whiskey-producing island) (Aye-luh) |

| For this question, it’s all about sounding the ‘ch’ as it is pronounced in ‘loch’ | |

| AUCHTERMUCHTY (a town in Fife) | AUCHENSHUGGLE (an area of Glasgow) |

A TALE OF TWO DICTIONARIES

(THE KEY TO UNDERSTANDING BRITISH/AMERICAN SPELLING DIFFERENCES)

We may share a mother tongue, but when it comes to spelling some common terms, we just can’t seem to settle on a shared favorite—or is it favourite?—approach!

The most common discrepancies between American and British spelling, (with the latter often prevailing as well in Canada, Australia, and other Commonwealth nations,) are:

- Words ending

in -OR in the USA and -OUR in the UK

behavior/behaviour,

color/colour,

favorite/favourite,

honor/honour,

neighbor/neighbour

- Words ending

in -ER in the USA and -RE in the UK

center/centre,

fiber/fibre,

liter/litre,

meager/meagre,

theater/theatre

- Words ending

in -IZE or –YZE in

the USA and -ISE or

-YSE in the UK take the

prize as being included alternatives in both dictionaries today.

analyze/analyse,

apologize/apologise,

organize/organise,

paralyze/paralyse,

realize/realise

So what explains these differences?

In the early years of the printing press, English spelling was much more variable than it is today and multiple versions of spelling co-existed.

SHAKESPEARE was perfectly happy to toggle between spellings, for example in 1598 he wrote ‘Love’s Labor’s Lost’ without the French ‘U’ and happily left out the second ‘A’ in his own name, writingShakespere.

Interestingly , he often preferred ‘center’ to the French-derived ‘centre.’

Dr. SAMUEL JOHNSON’S Dictionary of the English Language (1755) was the most ambitious of all previous attempts to compile a dictionary. In constructing it, he had made calculated decisions about which spelling variations to use.

Dr. Johnson could see that spellings such as ‘honour’ and ‘theatre’ were French-derived from the Norman Conquest. Johnson was no Francophile (he once proclaimed France “worse than Scotland in everything except its weather!”) but he thought there was an etymological justification for these spellings. The popularity of Johnson’s dictionary thus helped to cement ‘-our’ and ‘-re’ spellings as the BRITISH STANDARD SPELLINGS.

SPELLING AS A PATRIOTIC ACT

Meanwhile, in the newly independent United States, NOAH WEBSTER made his own mark on the English language through his widely read American Spelling Book (1783) and his greatly influential American Dictionary of the English Language (1828).

He particularly expressed distaste for words “clothed with the French livery,” Webster rejected the fussy -our and -re spellings that Johnson had helped elevate in Great Britain in ‘favor’ of the simpler -or and -er endings that made more phonetic sense. As a result, the latter became dominant in American prose.

So the DICTIONARY tells a fascinating story of its own about the global development of the English language and plays an influential role in shaping national preferences on both our sides of the Atlantic within the mighty ANGLOSPHERE.

And finally……

Noble Lords & Fair Ladies were asked to give any contributions for

Shakespeare’s SUPER-SPECIAL 5 Point Award for

BEST NEWLY-INVENTED WORDS of 2022 !!!!

Suggested words were tanniner (red wine with more tannin), zombulated (that feeling when…) overzoomed, kafter (short for look after), birdishly… and more that Sheila sadly didn’t manage to write down. The winning word was: Zombulated!

Zombulated won 5 bonus points for the Fair Ladies. Thus the score, which had been 43 to the Noble Lords and 39 to the Fair Ladies, became 43 and 44, and the cup was awarded (virtually) to the Fair Ladies Team. The Noble Lord nobly congratulated them., and we all thanked Lyndsay for an excellent talk!